With two deaf Polish immigrant parents, life for me as a first-generation American was more than just running around eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. It was more like kielbasa and sauerkraut with a side of mustard — but that’s beside the point.

My situation forced me to mature at a young age and learn to take responsibility in affairs I had no business taking care of. My parents could always read lips but Polish was much easier for them to understand. What couldn’t be understood in Polish had to be communicated through sign language. It was my job to translate. I would often make important phone calls on my parents’ behalf to credit card companies and billing agencies, attend my mother’s doctor appointments, and do my best to teach my parents English as I learned it.

If it weren’t for my dedicated preschool teacher who put in the extra effort to teach me English after the a.m. session concluded, I don’t know if I would have been able to attend kindergarten. I picked up English rather quickly without ever having to take an ESL course.

I knew I was different. In school, I felt different. I knew I was the only one with deaf parents and I didn’t really want anyone to know. I wanted to be like everyone else. I wanted to be normal. I wanted to have friends. I wanted people to like me.

My dad was the only deaf child in his school. He was in a sense different but he never felt that way. Though schools existed for the hearing impaired, the pace of learning wasn’t that of a standard school and my grandparents made the tough decision to go through intensive training with him so he could not only learn how to read lips and connect word to item, but also learn to properly speak as well. He was the fastest learner among his deaf peers and was even put on a stage in front of doctors to show the progress he’d made to a round of applause. My dad never learned sign language like the other deaf children in Poland. He simply didn’t need it.

My dad lived as if he could hear. He participated in every thing his hearing friends did — went on camping trips, hung out with the ladies, attended concerts — they didn’t think of him as any different because he wasn’t.

Neither was I.

If I could go back in time and change my mindset I would.

***

It was only when I started to become involved in sports that I finally felt a part of something. I felt as though I belonged. We all wore the same jerseys, competed for the same goal, and spent a lot of time together. I made tons of friends. I played PAL soccer, CYO basketball and Riverhead Little League as a child — then football, basketball and baseball for Riverhead as I matured through the school system.

My dad loved playing basketball. It was his favorite sport. I remember my dad and I would shoot hoops in the backyard when he had the time. He played on his school team but was limited in what he was able to do because he couldn’t hear. Vocal communication is a constant in basketball and if my dad wasn’t looking face to face with the play-caller or the coach, he would miss the play. He loved the game but lacked the true opportunity he wanted.

That’s when he heard of something he had no idea existed: an all-deaf basketball league. Unbeknownst to him, just about every major city in Poland had a team. They traveled around Poland and the league eventually crowned a state champion.

My dad, without hesitating, filled with curiosity, found out more information about when they play and peeked his head into practice. There they were, a court full of boys just like him, playing the sport he loved. After a tryout to determine if he was any good, the coach allowed him to join the team based in Krakow, Poland. There was only one problem: he didn’t know sign language. My dad was a lefty and had a pretty sweet outside jumper so the boys quickly started teaching him sign language. Soon enough he was able to compete and communicate and immerse himself in a culture that he was always a part of. If it wasn’t for the basketball team he may have never learned sign language. Those boys became his second family. They placed fifth his first year and then third his second. They got a medal for their accomplishment. But as the quality of life deteriorated in Poland, he made the decision to move to New York, leaving behind the sport he loved and friends he made to start a new life.

He’ll never forget his time playing just like I’ll never forget mine. I’ll never forget winning the only Long Island Championship for Riverhead as a member of the football team. I’ll never forget the bond we shared. We brought the community together that day and the friends I made on that team will forever be my family. Whether it’s Krakow or Riverhead or anywhere else in the world, a team breeds togetherness. And that’s a feeling that will stay with you for a lifetime.

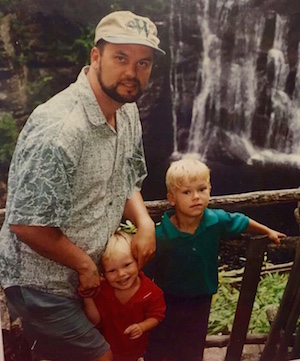

Happy 51st birthday, Dad.

Thanks for encouraging me to participate in sports. I couldn’t imagine my life without them. I even built a career out of it.

Michael Hejmej is a Riverhead native, a 2010 graduate of Riverhead High School and a 2014 graduate of Stony Brook University. He lives in Riverhead and writes for RiverheadLOCAL.com and SoutholdLOCAL.com.

The survival of local journalism depends on your support.

We are a small family-owned operation. You rely on us to stay informed, and we depend on you to make our work possible. Just a few dollars can help us continue to bring this important service to our community.

Support RiverheadLOCAL today.