Addie Mack Herzog was just over six months pregnant when the cramping started.

The baby had only recently begun kicking, so she wasn’t too concerned – it was late January, and she wasn’t due until May 1. She and her husband Geoff Herzog, who both graduated from Riverhead High School in 1998, had never had children before.

She didn’t think it was possible that she could be going into labor at 26 weeks.

But a trip to Stony Brook University Hospital revealed just that. Her water had broken. Without warning or preparation, Addie was thrown into the maternity ward in a dizzying whirlwind of doctors, medication and worst-case scenarios. She was now at major risk for infection. Baby Keegan, should he be delivered so early in the pregnancy, would have only an 80 percent chance of survival. His lungs were not yet fully developed. His tiny body would have a hard time managing its temperature; he would be at greater risk for brain hemorrhages and heart problems.

“It was so scary,” Addie said. “I had too much time to think about stuff. I tried to stay positive, but it was so nerve-wracking.”

The doctors at Stony Brook were able to stop her contractions and hold off delivery for another four weeks. Addie stayed in the maternity ward that entire time, taking time off from her job on family medical leave.

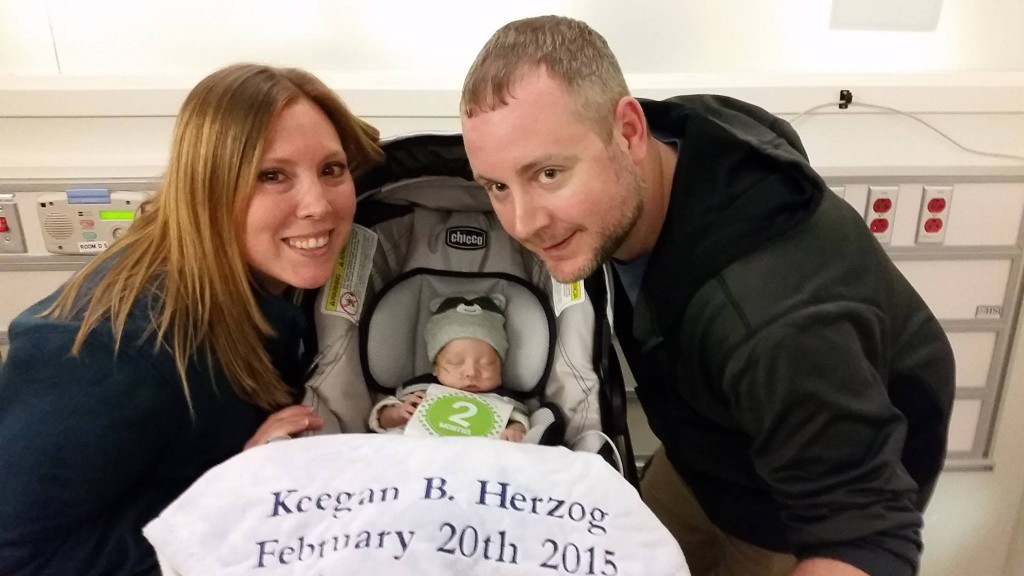

But by late February, Keegan had kicked his way to her cervix. There was nothing else the doctors could do. On February 20, 2015, Keegan Herzog was introduced to the world at just two pounds, 10 ounces. He was only 30 weeks old.

“As soon as I heard him cry, I started crying, too,” Addie said. “It meant he was alive.”

Keegan was delivered in an emergency cesarean section since he was positioned to come out feet-first, increasing the risk of mortality should he be delivered vaginally. Addie and her husband, Geoff, were only able to get a glimpse of him before he was whisked away to the neonatal intensive care unit, a hospital nursery for premature or sick babies.

It wasn’t another five hours before Addie was finished recovering from the c-section and able to see her baby in his incubator. And it would be an additional six days before she could finally hold him in his arms.

“It was a very different experience,” she said. “I had always wanted to have a kid, but it was a totally different experience from what I was expecting.”

Watching the doctors hook Keegan up to a ventilator in the delivery room, for example, was “a real struggle,” Addie said. “They had to put this tube down his throat,” she said. “I could tell it hurt him. He looked so upset. It was really hard to watch.”

But the real struggle began when she realized her maternity leave would end before Keegan was even home from the hospital.

While most mothers get to spend their maternity leave bonding with their newborns in the comfort of their homes, Addie did not leave Keegan’s side in the neonatal intensive care unit, where her baby lay in an incubator, struggling to breathe. Her leave ended a few days before Keegan was permitted to leave the hospital, two months after he was delivered.

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act allows for up to 12 weeks of family medical leave per year, but because Addie began her family medical leave when she was first admitted to Stony Brook in January, it ended up overlapping with her maternity leave, to her shock and dismay.

She was only home with Keegan for a few days before she had no more medical or maternity leave left on the state or federal level.

“For anyone who has a baby born with a medical condition, there’s no difference in the length of the maternity leave for a healthy baby or a sick baby,” she said. “It’s so frustrating.”

Even though Keegan was permitted to go home from the hospital, he still needed significantly more care and attention than a baby who was not born prematurely. He was still on oxygen and a monitor. His parents needed to bring him to five or six doctor’s appointments a week. “He sees 11 different kinds of specialists,” Addie said. “He’s on tons of different medications.”

Fortunately, Addie’s job gave her an additional four weeks of unpaid time off so that she could care for her infant.

But the day that her unpaid time off ended, Keegan was rushed into bilateral hernia surgery at Stony Brook. Addie took several vacation days to be there for his recovery.

“Any mother that has a baby with a medical condition, especially one that can’t leave the hospital like a healthy baby, should have their maternity leave extended for the time the baby’s in the hospital,” Addie said.

The United States is one of only three countries worldwide that doesn’t guarantee paid maternity leave, along with Oman and Papau New Guinea. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act, introduced in 1993, allows employees to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave.

Many states have introduced maternity leave policies beyond the Family and Medical Leave Act. New York’s maternity leave, which falls under short-term disability, allows a new mother to collect up to 50 percent of her average weekly wages, but only up to $170 per week.

And there are no extensions allowed in either federal or New York State law for mothers of children born prematurely, or with other medical conditions.

“On Long Island, people can’t just quit their job to take care of their baby,” Addie said. “I don’t even know financially how people can do that. I imagine it has to be a struggle.”

Fortunately, Geoff’s employer has allowed him to do a lot of his work from home since Keegan was born. Geoff works for a Connecticut company as a broadcast network engineer, so the extra time at home has been “a blessing,” Addie says. Her own employer has allowed her to work longer shifts two days of the week so that she can be home some extra days as well.

Keegan has been growing stronger all the time, she says. “It’s the one thing that’s made me stay positive,” she said. “The bigger he gets, the stronger he gets, he’s growing out of a lot of his issues. None of this will be permanent.”

His chronic lung disease could last up to two years, however. He won’t be able to go to day care, which Addie and Geoff had hoped to utilize since they both work. “He can’t be around any illnesses,” she explained. “It’s a life or death kind of thing.”

In the meantime, her friend Jeanne Minnick Smith has created a GoFundMe page for donations while Addie and Geoff struggle with reduced work hours and unexpected unpaid time off. The website has raised more than $5,000 to date.

“We are just speechless at how thoughtful everyone has been,” Addie said. “So many people from our graduating class have donated or reached out to us. It’s so nice to see how caring the community we grew up with is. When you go through a hardship, you realize how much support and love you have from your family and friends. That was one big positive through this whole thing.”

Meanwhile, Keegan gets bigger and better every day. He celebrated four months on Saturday during a belated baby shower. He would be only seven weeks if he had been born on time.

“It’s just such a shame that the government doesn’t provide any kind of assistance for people in these situations,” she said. “It makes me want to be an advocate for anyone who’s going through this, for anyone who has a baby born with a medical condition.”

The survival of local journalism depends on your support.

We are a small family-owned operation. You rely on us to stay informed, and we depend on you to make our work possible. Just a few dollars can help us continue to bring this important service to our community.

Support RiverheadLOCAL today.